There is no subject

but there ain't no object neither!

You’re reading DisAssemble, a philosophy of tech newsletter aimed at those interested in creating better digital products.

We are taught that there is a subject and there is an object.

They are separate. Binary.

This is a divide in philosophy and linguistics. But it exists - whether we are aware of it or not - in basically everything we do. It structures our thought and our language through an implicitly agreed upon pre-formulation.

Generally, we see a subject as something with subjectivity. That is, there is something that it is to be like that thing (to cite the philosopher Thomas Nagel). We can talk about being you, being me, being a dog, being a cat. There’s something that it is like to be those beings. In other words, they have some sort of consciousness.

A subject is usually a person. Indeed, personhood often defines subjects. Animals can be subjects as well, but we are very likely to objectify them (more on that in a second).

Subjects are individual and separate from other subjects and objects. I can discern myself as an entity by defining the parameters and boundaries of me. I am essentially everything that my skin contains, I might say. However, I tend to feel like my actual subjectivity, what I feel like my ‘perspective’ is, is somewhere in my brain.

We feel like we exist behind our eyes. What we are, all of our thought and being, occurs within our brains, somewhere in our synapses - or so we believe.

This seems to be a kind of metaphysics. We think we are a kind of energy. We might say ‘if you were me….’, as though we could jump between bodies. We somehow think our consciousness isn’t dependent on the particular organic patterning and makeup of our individual brains and bodies. Tenets of most, if not all, religion have done much to buoy this belief. Their metaphysics encourage us to believe that we are not bound to our bodies, but that our bodies are vessels for our spirits - our ‘true’ natures.

Because of this we feel we exist prior to interacting with the world - we are ‘always already’. That is, we exist in our circumstances, but we aren’t a result of them. We feel like we aren’t ‘relational’. We are encouraged to believe we are sovereign individuals - ‘you can be anyone you want to be’. You are a master of your being.

This is us. Subjects.

Then there are objects.

Objects are acted upon. They are perceived. They have no will. They are at best means to a particular goal of a subject. A hammer is an object used by a subject for an ends. An object is the opposite of the subject - it has no will - it is utterly non-autonomous - completely subject to the subject. This is why when we say people are objectified, it’s quite offensive. We do this to living beings all the time - both human and non-human organisms become objectified. What should be subject is often object. And for us, it’s one or the other - a binary.

We think of objects in this way - means to our ends - but an object isn’t just a tool, it is virtually anything material that isn’t a subject. A star, an atom, water - all of these are objects.

They can be moved about with impunity insofar as a subject can somehow find a way to do so. They can be dislocated from their surroundings and used in a way that benefits the subjects.

In other words, subjects can think about objects, analyse them, and act on them. But not vice versa.

This is the breakdown of the world into subjects and objects - the subject-object divide.

The belief in this divide means that we hold other beliefs that align with this divide as more ‘true’ or ‘accurate’. These paradigms then come to structure our lives.

Take capitalism. Capitalism is underscored by the subject-object divide through:

Seeing the world as objects to be extracted and used by us (subjects) - objects are there to be used!

Designing homogenised discrete, commodified objects in assembly lines, crops etc.

Detaching objects from where they originate and freely using them wherever and whenever (planting crops in areas they didn’t originate, for example)

Or take science. Science is underscored by the subject-object divide through:

Assuming subjects can be separated from the objects they examine (e.g., the scientist does not affect in observing)

Assuming subjects can rationally examine objects (e.g., any scientist at any time and any place will have the same result with the same technique)

Assuming subjects can access an ‘objective’, permanent truth about objects (i.e. we have access to a real, objective world and everything that exists can be verified)

We are taught there is a subject and object, then we engage in paradigms that reinforce this belief. Which comes first - the divide or the paradigms that use this divide? Perhaps this is moot - it is a feedback loop with no end or beginning. Regardless, the subject-object divide drives much of our activity, be it economic, epistemological, educational, or cultural.

But. And of course there is a ‘but’.

a) Maybe this subject/object divide is not good for us, or other living beings, and

b) Maybe it isn’t reflective of how we actually are in the world.

Now, I don’t need to go into too much detail for A). We could merely glance at the examples - capitalism and science - to see how A) holds true. I could quickly mention how objects that have value for us are seperated, taxonomized, engineered and cultivated in a homogenous way so that we can extract them most use out them. I might write a sentence about how we see everything as a ‘standing reserve’ of objects, including many beings that should be considered subjects in their own right. I could just pen a few words about how we subject some subjects to objectification, and thus unimaginable harm and death, thinking ourselves separate and objective (“for the greater good, we say"). I could quickly suggest that we excoriate those who reject the tenets of this divide, because this divide is correlated with progress.

But instead, I’ll focus on B) - is the subject-object binary even accurate?

Let’s say you were hungry.

If you had access to the internet you might order food. But if you had access to a kitchen you may want to cook food. Depending on the ease of access of each, and other material conditions, such as the existing food in your house or the distance from a place you want to order food from, you would make different decisions. Your immediate goals are formed by your context.

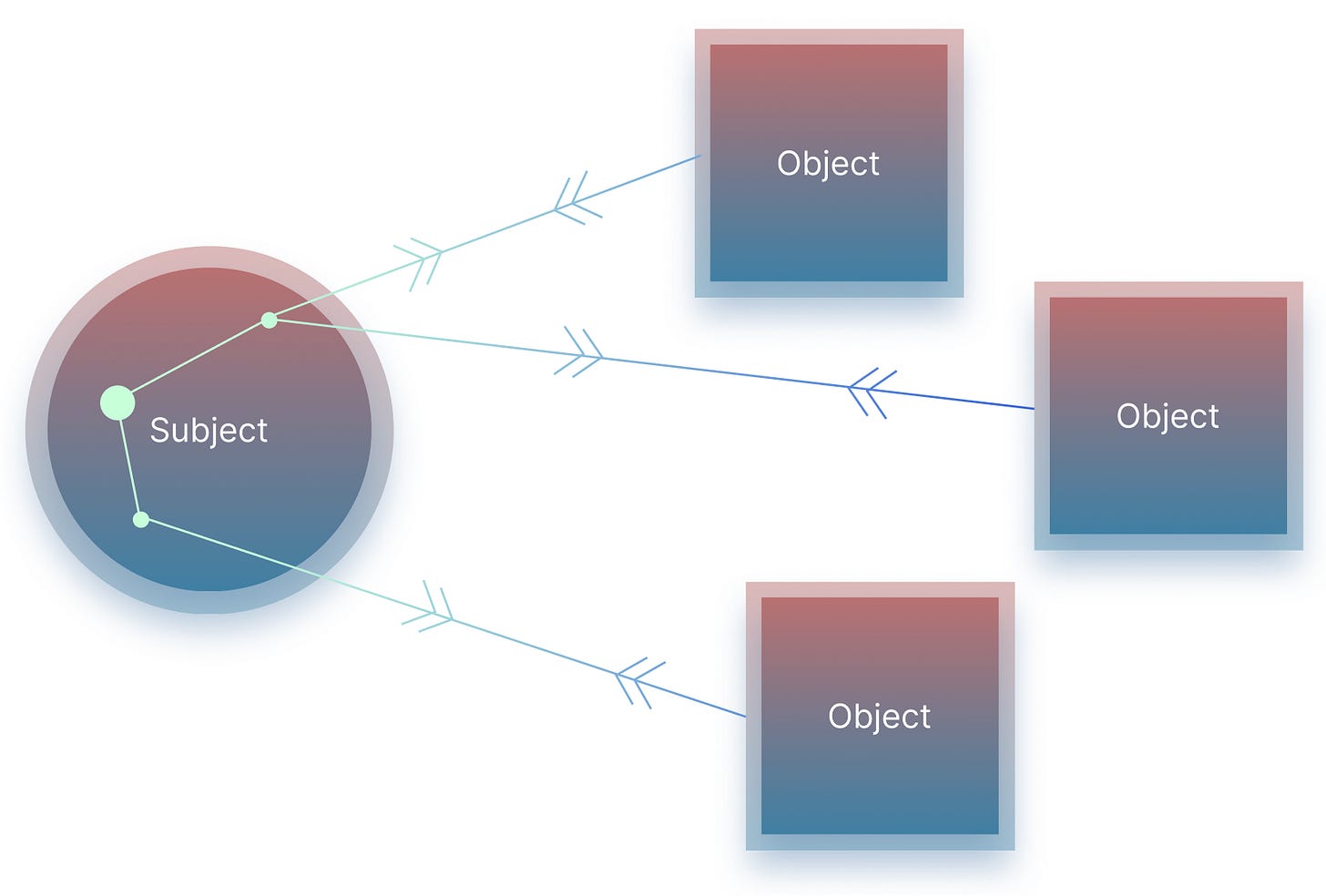

Objects can change your goals. They meld with people and form new goals. Bruno Latour discussed how objects and subjects form new ‘agents’ that have new goals that the subject or object wouldn’t have by themselves.

You become a kitchen-worker if you have access to a kitchen, whereas you become an internet-user if you have access to the internet. Your goals flex and mold depending on the type of hyphenated being you are, and in this way, you become a different being. Latour famously talked about how a person with a gun becomes a gun-man, able to enact goals (shooting someone) that they would not have access to otherwise.

We are always interacting with objects, we always have been interacting with objects since we were infants, and as such, they have been intrinsic to how we as ‘individuals’ (note the quotes) have become who we are. In other words, we have never been separate from objects. We are always hyphenated beings. Our goals, and our accustomization to certain goals are formed by our environment - by objects.

A second way the subject-object divide is inaccurate is through something I have written about several times before. We don’t nor have we ever thought exclusively within ourselves as subject - we think with objects. There are many ways we do this - consider notepads. Or closets. You might ‘remember’ things in a notepad. Or browse your closet as a means to ‘think’ about what to wear. Your memories are stored within these places. It’s often easier to remember using the world rather than relying on our own memory, which is hardly like the hard drive it is so often compared to.

This is called scaffolding, extending, enacting, embodying externalising or simply distributing our thoughts among the world.

A ‘subject’ such as it is, isn’t located entirely within itself. Instead, subjects - we - are spread through our environment, very literally. Our thoughts, our very being, are spread across objects. Our thought is more like an open container, with feedback loops between ‘objects’ and ‘subject’.

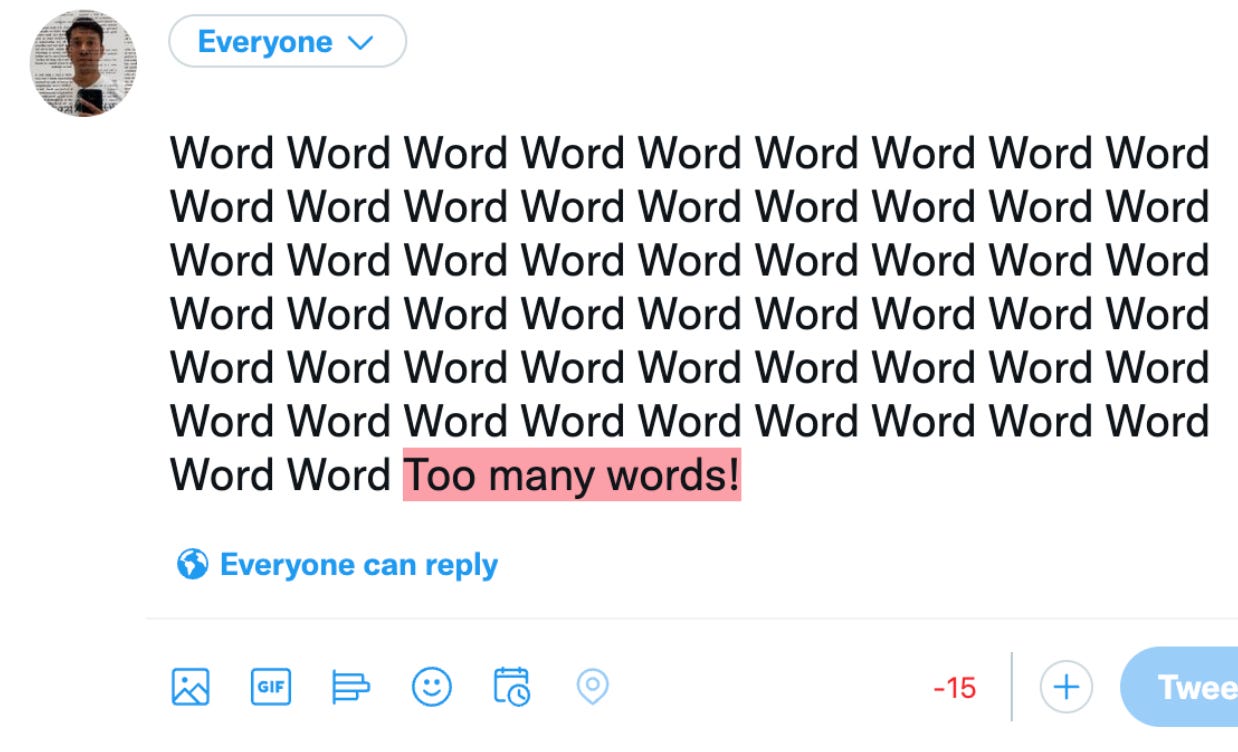

Finally, we can see how objects shape what we do. Consider how a bench affords, or allows sitting but discourages sitting too long by not being too comfortable. Consider how Twitter, affords, or facilitates, shorter messages but refuses longer messages.

These are perceived ‘interaction potentialities’, which are called affordances, which I have also written about and interviewed very smart people about.

The psychologist JJ Gibson coined the concept. He said we don’t perceive objects, but rather what he called affordances. A hole, for example, affords storing stuff, falling into, or even hiding - but other objects can afford these actions as well. For example, you could hide also in a shed or behind a tree. We see the world and its objects are relevant to what we can do and to what extent we can or can’t do that action.

And moreover, each activity we undertake opens up new opportunities and constraints. A painter for example, sees different opportunities for action based on the last thing he painted, a developer sees new actions or new constraints based on the latest bit of code that she wrote. Or take design. You aren’t just externalising what you think about, you are manipulating your ‘thoughts’ in real time. You move the design elements around, reflecting on what you’ve done. New constraints, opportunities, and ideas emerge in feedback loops with the object-designs around you. Every time we change the world, the world speaks to us, different.

Objects, then, aren’t separate and inert tools, but bursting with potential that are relationally connected to us - subjects - shaping how and what we can do/think.

The subject-object divide as it stands is ultimately inaccurate in terms of how we are. It’s a failure of imagination. And its effects stretch beyond capitalism and science. It stretches into design, and how we design technology.

How? More on that next time.

Stay well.